Since the beginning of humanity's existence, its development has been largely associated with the use of different forms of energy, depending on availability at each time and place.

Electric energy is, without a doubt, a vector for the social and economic development of a country.

The map of electrical exclusion in Brazil reveals that families without access to energy are mostly in locations with the lowest HDI (human development index) and in low-income families (Brazil, 2019).

Furthermore, it is known that the studies carried out to evaluate these items do not consider gender inequality, that is, “most data implicitly assume an equal distribution of resources among household members, which would tend to underestimate poverty among women” (IPEA, 2017).

Brazil took a while to “leave” the monoenergetic vision when compared to other countries due to the abundance of water it has.

However, due to the 2001 blackout, a new stance had to be adopted, and as a result, wind energy is now already established and solar photovoltaic energy is growing exponentially.

Likewise, there is evidence that diversity in important decision-making spaces increases the efficiency of the science produced itself (Nielsen et al., 2017), as the diverse and plural vision enriches the possibilities and increases the number of solutions, which It even leads to impacts on the economic world (Hunt et al., 2015).

Considering the 17 objectives for sustainable development proposed by the United Nations (UN, 2015), it is identified that the use of solar energy and the eradication of gender inequalities are represented by more than half of these (8 of the 17 objectives).

The Global Women's Network for the Energy Transition (Global Women's Network for the Energy Transition – GWNET, 2020) states that “diversity and inclusion are paramount in the transition to renewable energy. If gender diversity is not prioritized, changes will not occur.”

According to data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE, 2019), the Brazilian population is made up of 51.7% women, who are also the majority with higher education degrees. On the other hand, women's salary is, on average, 75% of men's salary.

Furthermore, according to data from IBGE (2019), another fact to be highlighted is that in Brazil only 10.5 % of seats are occupied by women in the chamber of deputies, while in the world women occupy 23.6%.

In the scientific area, 49% of the production is published by women (Agência Brasil, 2019), however this data must be evaluated analytically, as approximately 100% of the articles have male authors. In the field of engineering, only 29% of researchers are women.

Following the trend, with regard to the number of jobs, in exact sciences 32% are occupied by women and in engineering the number is slightly higher, at 39% (Bolzani, 2017).

Furthermore, when analyzing the spaces of leadership and protagonism there is an evident under-representation of women. For example, the number of women holding CNPq 1A research productivity scholarships in the area of exact sciences/engineering is low, at just 20% (Inep, 2016) (Valentova et al., 2017).

It is observed that the percentage of women decreases disproportionately as one advances in one's career, a phenomenon known as vertical or hierarchical segregation (Rossiter, 1982), popularly known as the scissors effect. For all scientific-technological areas, a similar situation is found: despite a relevant presence, women have little or no visibility in strategic positions.

Motherhood is a factor that also explains the difference between women in stable and prestigious positions in scientific careers (Freeman et al., 2009), as women with children have less chance of reaching these positions in all areas of knowledge (Mason et al., 2013) and it is known that for a period of up to 4 years after motherhood there is a decrease in productivity of researchers (Andrade, 2018).

In the energy sector, the predominance of men is also noted. According to a survey carried out by IRENA (2019), worldwide, women occupy 32% of jobs in the areas of renewable energy.

In non-renewable energy, this number drops to 22%. This difference may be due to the fact that the renewable energy sector has a more multidisciplinary dimension than the non-renewable sector. Still, even though women have a greater participation in renewable energy, the gender imbalance in the energy sector is quite prominent.

This imbalance is reflected in decision-making forums. As a consequence, the invisibility of women working in the sector discourages girls from studying science and/or engineering. The challenges are urgent and inescapable.

To fill this gap and encourage the participation of more women in the energy sector, the formation of many organizations has been observed worldwide that defend gender equity and balance in the sector.

Women's organizations in the sector have also increased in recent years, aiming to raise society's awareness of gender issues and to boost women's activities in the area.

A very relevant and strong example of action is GWNET (2020), an international network established in 2017 that aims to advance the energy transition through the empowerment of women who work in the energy sector with the formation of networks of networking and mentoring and training programs.

In Brazil, there has been a tendency towards an increase in the role of women in the energy sector. For example, at the VII Brazilian Solar Energy Congress (CBENS), in 2018, 27% of the participants were women.

This number is significant compared to other numbers mentioned above, but it is still a small fraction in the sector. With the aim of making visible women leaders in the scientific, technological, business and industrial fields, and showing alternative models to those generally publicized in the media and promoting changes in our work environments, the Brazilian Network of Women in Energy was formed Solar (MESol Network).

The MESol Network seeks to connect women in the sector to discuss opportunities and challenges faced, as well as promote actions that encourage the inclusion and retention of women in the area.

It is known that the lack of a network of contacts of women in the area and references of women's success in the sector corroborate the low presence and small leadership of women in the energy sector.

Therefore, this article aims to show the reality of women in the solar energy sector, proposing a diagnosis of the scenario of gender inequality in Brazil through the results obtained by the Brazilian Network of Women in Solar Energy, in addition to discussing the possible consequences of such data.

Brazilian network of women in solar energy

The MESol Network was formed after the 1st Meeting of Women in Solar Energy, in June 2019, at the Fotovoltaica Laboratory-UFSC. The network is made up of a group of women with scientific and technical training who research, teach and work in the area of solar energy conversion.

It was formed around a shared diagnosis of gender inequality in the workplace, with the intention of analyzing its causes and developing proposals to improve this situation.

The network also shares the vision of the need to move towards a new renewable, clean, distributed and democratic energy model. He believes that solar energy should be a fundamental pillar of this future model.

Not only because it is a renewable technology, which does not produce waste or emit CO₂ and whose cost is already similar to that of other traditional sources, but also because it has two fundamental characteristics for this new model.

First, solar radiation is a geographically distributed resource, especially available in areas of the planet where the majority of the population lives without access to electrical energy. Second, the modular nature of solar energy, particularly photovoltaic technology, allows for the development of distributed systems.

This aspect allows citizens to become producers of the energy they consume, democratizing the electrical system, reducing pollution in cities and increasing our energy sovereignty.

As a first action, the MESol Network created a form containing open, multiple-choice and dichotomous questions about the identification and description of respondents, as well as experiences and opinions about gender inequality in the sector.

Specific questions about motherhood were also prepared, answered only by respondents who are mothers. In this way, it was possible to obtain quantitative and qualitative results about women who work in the area of solar energy in Brazil.

O online form was emailed to a contact list of 419 women in the industry and received 132 responses in less than three months. To obtain a greater number of responses, the questionnaire was kept short, requiring less than 15 minutes to complete, and remains available so that more women can answer it, aiming to contemplate the diversity that exists throughout the sector, and subsequently allow dissemination of the most realistic results possible.

No personally identifiable information was used, so there are no confidentiality issues.

Results obtained by the MESol Network questionnaire

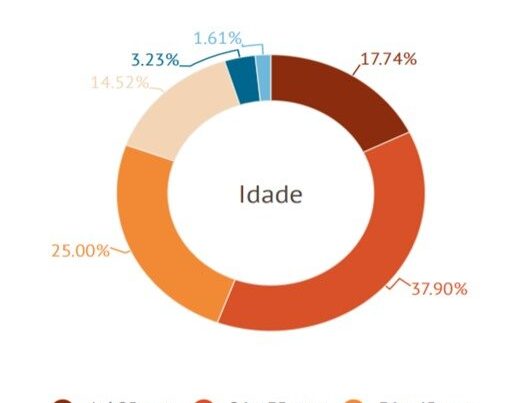

Figures 1 and 2 show the results of the interviewees' profile. Figure 1 shows the age and Figure 2 shows the distribution by work sector of the participating women. The majority of respondents are between 26 and 35 years old and a very small proportion are over 56 years old.

This can be explained by the growth in installed power in photovoltaic plants and systems connected to the grid (BEN, 2019), which is relatively new in Brazil due to distributed generation, and by the greater dissemination of the online questionnaire among young people, but it can also corroborate the idea of vertical segregation, explained in Rossiter (1982).

Regarding the sector in which the research participants work, there is an almost equal distribution between women who work in private companies and in teaching and research, with women even working in both sectors.

Among the questions about motherhood, it was identified that 42% of the respondents are mothers. Among them, 47% had support from their supervisor, advisor or boss to continue breastfeeding after the end of maternity leave.

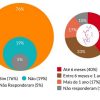

Figure 3 shows the breastfeeding status of the responding mothers. The graph shows that only 76% of the responding mothers were breastfed on demand. Of these, 40% breastfed for up to six months, 36% breastfed between six months and one year, 17% for more than a year and 10% did not answer this question.

Identifying the role of the MESol Network in the sector is undoubtedly a major challenge because, as previously mentioned, there are several problems in relation to the topic.

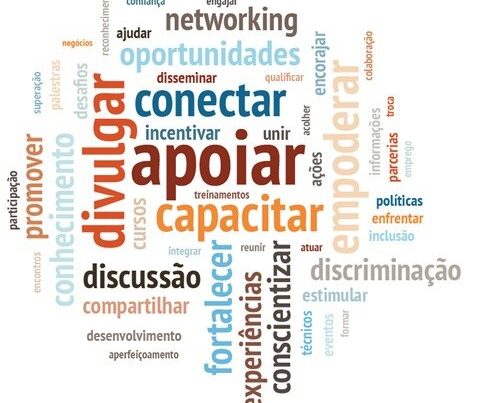

Therefore, one of the questions in the questionnaire was “In your opinion, what should be the role of a network of women in solar energy?”, and through this different answers were obtained and included in a tool web intuitive visualization – Infogram (2020) – through keywords.

You can identify in Figure 4 the words that were most mentioned in a larger size, and the least mentioned in a proportionally smaller size.

It appears that the word that has the greatest representation is “support”, which highlights the fragility of the sector and the importance of the network for these women.

When evaluating the answers to the question “Have you ever heard sexist comments because you are a woman in a predominantly male work environment?”, it was found that 62% of the interviewees had already heard comments of this nature and 49% stated that they had already suffered some type of discrimination because they were women in the solar energy sector.

As an open response in the form, several actions/ideas were obtained that were listed by the participants, and that the MESol Network believes that if put into practice they can contribute to improving the working conditions of women who work in the sector, these being: conversation circles and round tables on the topic with men participating, courses with places reserved for women, groups on social networks just for women (to seek services and support each other's work), initiatives in companies to encourage gender equality, public competitions and tools for selecting candidates in private companies with double blind, shared six-month maternity leave, companies with daycare for children up to 3 years old and that allow breastfeeding, consideration of maternity leave time for evaluation in research projects and grants and public competitions, appreciation of female leaders in management positions, specific lines of financing and leadership and prevention and agility on gender-based violence and sexual harassment, among other things.

Conclusions

The diversification of the energy matrix and gender diversification prove to be effective solutions to resolve the main challenges in these areas, as they include the union of strategies dedicated to building unique growth.

As a first action, the Brazilian Network of Women in Solar Energy prepared a form to identify and describe the respondents, as well as experiences and opinions about gender inequality in the sector. In this way, it was possible to obtain quantitative and qualitative results about women who work in the area of solar energy in Brazil.

As stated before, when evaluating the answer to the question “Have you ever heard sexist comments because you are a woman in a predominantly male work environment?” It was found that 62% of the interviewees had already heard comments of this nature and 49% stated that they had already suffered some type of discrimination because they were women within the solar energy sector.

Thus, the network identifies the need to seek ways to support women who feel helpless, discriminated against and devalued, making them capable of establishing their active participation in the Brazilian energy transition process.

Thanks

The authors would like to thank all participants in the Brazilian Network of Women in Solar Energy, the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) and the Brazilian Solar Energy Association (ABENS) .

References

- Andrade, RO, 2018. Motherhood in the Curriculum. Revista Pesquisa Fapesp, 269. Available at: http://www.revistapesquisa.fapesp.br/2018/07/19/maternidade-no-curriculo. Accessed on: November 19, 2018.

- Agência Brasil, 2019. Women sign 72% of scientific articles published by Brazil, 2019. Available at: . Accessed on: December 6, 2019.

- BEN, 2019. Energy Research Company. National Energy Balance: Summary Report, base year 2018. Rio de Janeiro: Ministry of Mines and Energy.

- Bian L, Leslie S, Cimpian A., 2017. Gender stereotypes about intellectual ability emerge early and influence children's interests. Science, pp. 389-391.

- Bolzani, VS, 2017. Women in science: why are there still so few of them? Brazilian Society for the Progress of Science. Science and Culture. vol.69, no.4. Available in: . Accessed on: December 1, 2019.

- Brazil, 2018. Higher Education Improvement Coordination Foundation. Official Gazette of the Union, 10/01/2018. Ordinance 221 of 09/27/2018.

- Brazil, 2019. Light for All Program of the Brazilian Ministry of Mines and Energy, available at: , Accessed on: December 26, 2019

- IBGE, 2018. Number of men and women. Available in: . Accessed on: November 4, 2019.

- IRENA, 2019. Renewable Energy: A Gender Perspective. Available in: . Accessed on: November 4, 2019.

- Elsevier, 2017. Gender in the Global Research Landscape, Analysis of research performance through a gender lens across 20 years, 12 geographies, and 27 subject areas, 2017. Available at:

- nal_for-web.pdf>. Accessed on: November 20, 2018.

- GWNET, 2020. Global Women's Network for the Energy Transition. Available at: < https://www.globalwomennet.org/>. Accessed on: February 20, 2020. Hunt, V., Layton, D., Prince, S., 2015. Diversity Matters, McKinsey & Company, February. Available in: . Accessed on: November 20, 2018.

- INEP, 2016. Higher Education Census Statistical Notes. Available in: . Accessed on: November 20, 2018.

- Infogram, 2020. Intuitive visualization tool. Available in: . Accessed on: January 10, 2020.

- IPEA, 2017. Institute for Applied Economic Research: Human Development Beyond Averages. Brasília: UNDP: IPEA: FJP. 127 p. ISBN: 978-85-88201-45-3. Nielsen MW et al., 2017. Gender diversity leads to better science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Feb 2017, 114 (8), pp. 1740-1742; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1700616114. UN, 2020. Sustainable Development Goals, 2015. Available at . Accessed on: February 26, 2020.

- UN, 2019. Unconscious Biases, Gender Equity and the Corporate World: Lessons from the Unconscious Biases Workshop, 2016. Available at: < http://www.onumulheres.org.br/wp

- content/uploads/2016/04/Vieses_inconscientes_16_digital.pdf>. Accessed on: December 4, 2019.

- Rossiter, M.W., 1982. Women Scientists in America: Before Affirmative Action, 1940-1972. 2. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801857119. Valentova, JV, Da Silva ML, Otta, E, McElligott, AG, 2017. Underrepresentation of Women at the Senior Levels of Brazilian Science. Peer J. 5. 10.7717/peerj.4000.

Authors

- Aline Cristiane Pan – Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Energy Management Engineering

- Aline Kirsten – Federal University of Santa Catarina, Photovoltaic Laboratory-UFSC Brazilian Solar Energy Association (ABENS)

- Kathlen Schneider – Federal University of Santa Catarina, Photovoltaic Laboratory-UFSC Institute for the Development of Alternative Energies in Latin America (IDEAL)

- Izete Zanesco – Brazilian Solar Energy Association (ABENS). Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul, Polytechnic School, Solar Energy Technology Center (NT-Solar)

Original article from VIII CBENS 2019