Article written in collaboration with Bruna Cattoni*

With the exponential growth of the solar energy sector in Brazil, which currently has more than 9 GW of installed power, issues related to law arise every day, following the entire maturation and development of this market.

This article will address the issue of the dangerousness of activities carried out by employees exposed to electrical energy generated through photovoltaic systems during the construction, operation and maintenance phases of plants, based on the most common questions on the subject.

Initially, it is important to differentiate the construction and operation phases of solar energy plants. The process of building a plant is complex, with several stages that have specific risks.

Prior to the construction process, a feasibility analysis of the project is carried out, which is based on four main pillars, namely connection feasibility analysis, project technical feasibility, land tenure regularization and environmental compliance.

From the moment that all the pillars present desirable viability, the initial construction phase of the project begins, which basically consists of actions necessary to enable the installation of the equipment.

This stage involves setting up the construction site, creating access, installing a fence, removing vegetation and, in some cases, earthworks.

After preparing the land, the mechanical phase begins with soil drilling, foundations, pile driving, structure alignment and, in some cases, concreting. Mechanical assembly processes vary directly with the type of structure to be adopted and its model.

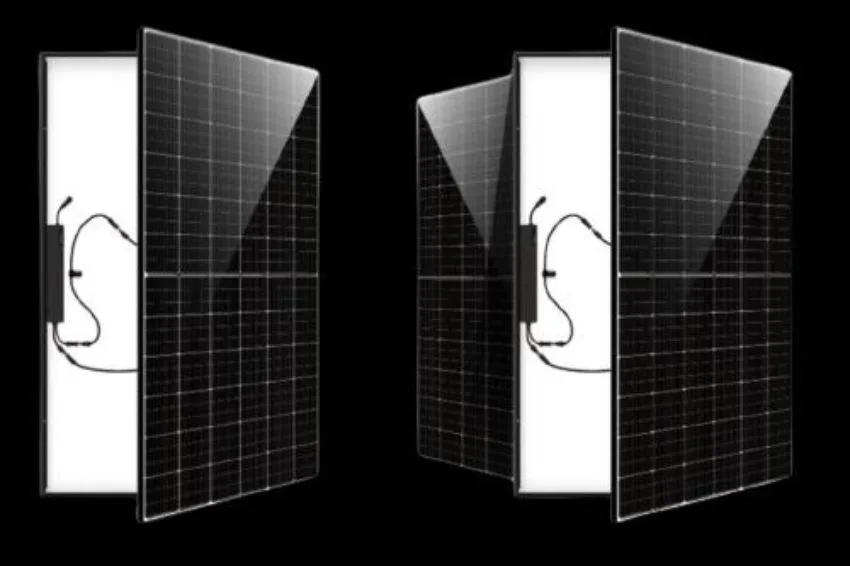

The modules are fixed to trackers (which are movement systems that increase the energy capture efficiency of solar panels as they track the sun) or to fixed structures using clips and are electrically arranged in series in order to check the voltage and power defined in the project.

The string cables (series of modules) are routed through the module support structure, undergoing parallelization in specific string boxes (junction boxes) or in the inverters themselves.

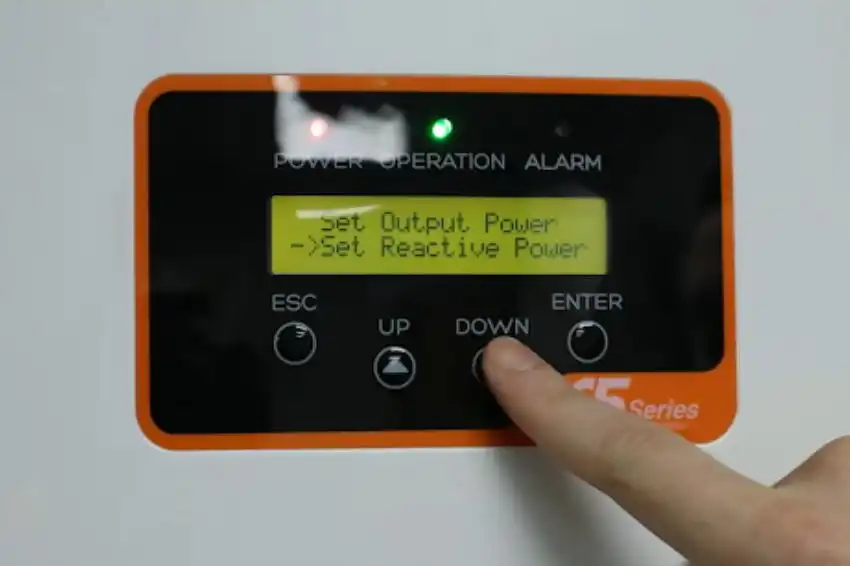

Inverters can be installed in a decentralized or centralized manner within an electrocenter or a unitary substation, where transformers, measuring equipment and protection devices are also installed.

The transformers raise the voltage levels to medium or high levels and from there the circuits direct the energy to the internal substation that allows the connection of the enterprise and the flow of energy.

It should be noted that the project is only energized after cold commissioning, a step responsible for verifying the compliance of all installations. Only in the post-construction phase does operation take place, when the plant is connected to the grid and starts producing electrical energy.

During the operation of the solar plant, it is considered a SEP (Electrical Power System), which is defined as the set consisting of electrical plants, transformation and interconnection substations, lines and receivers, electrically connected to each other, that is, they are large energy systems that encompass generation, transmission and distribution of electrical energy.

Although the solar power plant is considered SEP, it is certain that solar panels require minimal maintenance, as they are considered very safe systems.

Furthermore, it is important to differentiate the SEP from the SEC (Electrical Consumption System), which is the electrical network located after the measuring clock and is considered low voltage.

Keeping in mind the specificity of each phase, we began to analyze the issue of danger involving the construction, operation and maintenance activities of photovoltaic systems.

What is dangerousness?

The term “hazardousness” derives from the word “danger”, and in labor law, the term is used when an employee is constantly exposed to agents that can cause harm to life or physical integrity.

In the case of workers in the solar energy sector, they are potentially exposed to a variety of risks, such as arc flashes, electric shocks, falls and risks of thermal burns that can cause injuries and even death.

External factors that contribute to risk exposure are also highlighted, such as hailstorms, fires and short circuits that cause damage to electrical installations and that can create circuit paths, propagating along the structure and system racks. until it reaches the worker.

Thus, employees who work exposed to electrical energy, as a general rule, are entitled to an additional salary for exposure to electrical risk, the so-called hazard pay.

Additional hazard pay

Paragraph 1 of article 193 of the Consolidation of Labor Laws (“CLT”) states that working under hazardous conditions guarantees the employee an additional 30% on top of their salary, without any additions resulting from bonuses, prizes or participation in the company's profits. , which can be increased by agreement with the category union.

However, the questions that remain are: Are all employees who work in solar energy plants entitled to receive hazard pay? And in what situations is the additional due?

Norms that regulate dangerousness

Before tackling the proposed topic, it is important to highlight the rules that regulate the payment of hazard pay and its exceptions.

According to the wording of article 193, I of the CLT, dangerous activities or operations are those that, due to their nature or work methods, imply a high risk due to the permanent exposure of the worker to flammable, explosive or electrical energy.

Additionally, Precedent No. 364, I of the TST (Superior Labor Court) makes it clear that employees who are permanently exposed or who, intermittently, are subject to risk conditions, are entitled to hazard pay. Undue only when the contact occurs occasionally, thus considered fortuitous, or which, being habitual, occurs for an extremely short period of time, according to jurisprudence up to 10 minutes per day.

Jurisprudential Guideline No. 324 of Subsection I Specialized in Individual Disputes (SBDI I) ensures the payment of hazard pay only to employees who work in an electrical power system under risky conditions, or who do so with electrical equipment and installations. similar ones, which pose an equivalent risk, even in an electrical energy consuming unit.

Furthermore, attention must be paid to the NRs (Regulatory Standards) issued by the extinct Ministry of Labor and Employment (“MTE”), which are a set of mandatory technical provisions and procedures related to the safety and health of workers in certain activities.

The objectives of the NRs are to instruct employees and employers regarding the necessary precautions that must be taken in order to avoid workplace accidents or occupational illnesses, preserve and promote the physical integrity of workers, establish regulations relevant to occupational safety and health and promote occupational health and safety policy in companies.

To minimize the risks of exposure to electrical energy, NRs 10 and 16 were published, which provide, respectively, for the implementation of control measures and preventive systems, in order to guarantee the safety and health of workers exposed to risk factors. resulting from the use of electrical energy, and identifies which activities are considered dangerous and subject to payment of the hazard pay provided for in the CLT.

NR10: Safety in electrical installations and services

NR-10 applies to the energy generation, transmission, distribution and consumption phases, including the design, construction, assembly, operation, maintenance of electrical installations and any work carried out in their vicinity.

According to the standard, only authorized people with specific and mandatory training, with a curriculum established by NR itself, can access and work in electrical installations.

This standard provides for collective protection measures, such as de-energization and safety signaling through cones, chains, safety strips, signage signs, sirens, alarms and light alerts, containment grids, padlock-type locks and claws that serve to prevent the restart of machines, equipment or electrical panels during the maintenance period, ventilation and exhaust system to eliminate contaminating gases, vapors or dust, better known as Collective Protection Equipment (“EPCs”).

Furthermore, it establishes the need to use Personal Protective Equipment (“PPE”), such as a hood or balaclava to protect the head, ear protectors and noise mufflers for hearing protection, glasses and visors to protect the eyes and face. , gloves and hoses to protect hands and arms, masks and filters for respiratory protection, vests and overalls to protect the body, shoes, boots and boots to protect legs and feet.

Annex 4 NR-16: Dangerous activities and operations with electrical energy

Item 2 of Annex 4 of NR-16 states that the payment of additional hazard pay is not due in the following situations:

- a) in activities or operations in the electrical consumption system in installations or electrical equipment de-energized and released for work, without the possibility of accidental energization, as established by NR-10;

- b) in activities or operations in electrical installations or equipment powered by extra-low voltage;

- c) in elementary activities or operations carried out at low voltage, such as the use of energized electrical equipment and the procedures for turning on and off electrical circuits, provided that the electrical materials and equipment comply with the official technical standards established by the competent bodies and , in the absence or omission of these, the applicable international standards.

When to pay the hazard pay premium?

Returning to the initial question, considering that the legislation provides exceptions in which the hazard pay is not due, it must be analyzed on a case-by-case basis.

However, as a rule, considering that, as seen previously, when solar plants are built, photovoltaic panels produce very low voltage, there is no way to consider that the plant is a SEP, which is why, according to the aforementioned legislation, It can be stated that employees are not exposed to the risks of electrical energy, and consequently there is no justification for paying hazard pay for any employee during this phase.

Regarding the operation and maintenance phase of solar plants, considering that the legislation is clear that there is only a risk to the physical integrity or life of the employee when he is, in fact, habitually working in an energized SEP. , which, as a general rule, does not occur, it is understood that the absence of payment of hazard pay at such a stage is justifiable.

It should be noted that, normally, maintenance of photovoltaic systems is carried out by qualified professionals, on a scheduled basis and with the equipment de-energized, in compliance with the NRs, which means that such employees do not have contact with electrical energy and consequently do not have the right to receiving hazard pay.

Furthermore, it is important to highlight that even in the event of the need for eventual emergency maintenance on the photovoltaic system, during the operation phase, it is understood that this is a fortuitous fact, which, according to applicable standards, excludes the obligation payment of hazard pay for the employee responsible for maintenance, given the absence of customary conditions.

Finally, it is clarified that employees who only work at the solar plant, but do not have any contact with the photovoltaic system, are not entitled to payment of hazard pay, considering the complete and total absence of risk to their life or integrity. physical.

*Project Manager at Greenyellow do Brasil, Renewable energy engineer graduated from FUMEC, and MBA in Project Management from the same institution.

7 Responses

I live on a site where a solar plant is being installed. Is there a risk to my family's health? Since it is close to 100m from my residence.

It has voltage, current, and certainly power.

Isn't that SEP?

Imagine a defective board, leakage current, and it is already in series?

During the execution of the project, regardless of the functions, it requires reports and effective protection measures, otherwise, the danger is due.

Congratulations on the topic covered. Although focused on MINI Generation, from what I understand, I understand that the concerns are also valid for MICRO Generation. I would add, if I may, the NR-35 Work at Height, which in my opinion, would also produce danger. Check?

I have to disagree with the premises presented in the article. It is true that the voltages on plates alone are low voltage, but when strings and string boxes are assembled, the voltages rise to close to 1000v. Requiring specific knowledge of direct current, with an effective risk of electrical discharges and arcing resulting from inappropriate handling or assembly operations. Another important factor to consider is working at heights linked to the activity. It can be argued that the entire mechanical assembly stage of the system is free from electrical risk. However, I understand that in the electromechanical connection stages of the DC and AC systems, there is an important risk, carried out in a routine and necessary manner, with the need for knowledge, planning and risk mitigation. The interpretation that photovoltaic systems are free from risk is fallacious, as I see it as inherent to the activity, not only in the execution stage but also in the operation and maintenance stage. Just remembering, the power systems are also assembled and maintenance operations are generally carried out with the systems de-energized.

Doctor, good morning!

Just passing by to make some considerations that must be observed in relation to the definition of risk and payment of hazard pay in SFV.

Ordinance 3,214/78 defines the parameters of NR 10, however it is an “old” standard that is more focused on alternating current, and not comprehensively targeting direct current.

It is a new subject, and this activity has increased since 2016.

The determining factor for the elimination of dangerousness payments is the issuance of the dangerousness report, provided for in NR 16, by a doctor or occupational safety engineer. Or request an expert directly from the MT, where you will be informed whether or not the risk exists.

In the preliminary risk analysis, we must assess that, when installing a photovoltaic module (technical basis for legal support), it already starts to generate energy, even if the sun is weak or in cloudy weather and, therefore, it is important that we have the necessary Be careful, as there is no “de-energization” protection of the circuit

(technical basis for legal support).

In this case, for risk analysis, work on energized circuits must be taken into account. However, energized work for this application requires knowledge of voltage and direct current, that is, the same existing rules cannot be used, for example, in the current NR-10 which is more focused on alternating current. (technical basis for legal support).

One of the most striking and important characteristics of direct current is the electric arc generated when opening switches and/or connections (technical basis for legal support). This condition must be properly studied, as the culture of direct current is practically unknown and is seen only as a vehicle battery, but we know that a failure in a connection, for example, can generate a large electric arc and, therefore, start a large fire (technical basis for legal support). This concern must be part of the risk analysis process, but before that it must be the reason for study in the design of this type of installation.

https://revistamundoeletrico.com.br/seguranca/seguranca-nos-servicos-de-sistemas-solares-fotovoltaicos/

https://www.enfoquems.com.br/artigo-seguranca-em-sistemas-fotovoltaico/

Although the modules alone generate a low voltage, when they are connected in series in the string, they generate voltages that reach around 1000V, for the workers who make this interconnection, are they not entitled to pay hazard pay?

I believe that danger only exists where there is a difference in electrical potential, hence the emergence of electric and magnetic fields.